Earlier, I considered how Hillary Clinton would fare in a presidential primary. Of course, whoever wins the Democratic primary will have to face a Republican nominee. The Republican National Committee is currently meeting in Hollywood to discuss their strategy in the aftermath of President Barack Obama‘s reelection in 2012. But we don’t even know how meaningful Obama’s victory is, in terms of what it means for future elections.

The 2012 Presidential election can fit three historic narratives. We won’t know for some time which summary is the most accurate.

I tend to agree with the middle of the road narrative. The United States has a two party system in which there’s currently a level of parity between Democrats and Republicans. Since Dwight Eisenhower, the following tendency has predicted 14 out of 16 presidential elections: Voters select a party for two terms in the White House, and then go and pick the other guys. Obama’s victory, while Republicans kept the House and expanded their number of Governors from 29 to 30, fits this version. It’s possible that at some point we’ll have a realigning election giving one party dominance like the Republicans had after the Civil War, and Democrats had after the Great Depression, but it hasn’t happened yet.

Then there’s the argument that favors Democrats. Bill Clinton seized the center in 1992, and we’re already in an era of Democratic dominance. Since then, Democrats won three landslide elections and one close election (and the electoral vote wasn’t all that close), while Republicans won one close election and one possibly fraudulent election. Meanwhile, the changing demographics of the country, as 50,000 Hispanic-Americans become eligible to vote every day, as well as changing views on social issues, are just making the electorate more and more liberal. Republicans will win a few presidential elections, as Grover Cleveland and Woodrow Wilson did in the otherwise Republican era from 1860-1928, and Eisenhower did in the Democratic era from 1932-1964. They may even keep the House, thanks to gerrymandering, the financial advantages of incumbents and a tendency of Democrats to live close to like-minded people. But the next Presidents are more likely than not to be Democrats.

A conservative version of this narrative is that the nation is becoming more redistributionist, and that is why Democrats now have the edge.

There is also the argument that Barack Obama’s race cost him several points in the popular vote in 2008 and 2012. If this were true, it masks the strength of Democratic candidates for office.

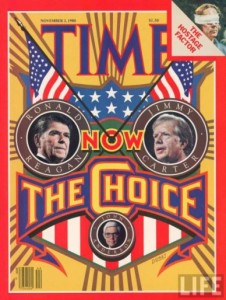

The least convincing claim is that this is still an era of Republican dominance. By this argument, after liberalism died with LBJ, Republicans have won 7 of the last 12 presidential elections, and the party is favored to win the next two, as it has been three generations since Democrats held the White House for more than two terms. Democrats only get the White House under the right set of circumstances. Their only successful nominees since Nixon have been Southern Governors, or a rare candidate who fit a very specific demographic sweet spot: a Midwestern African-American elected to statewide office. And the only Republicans who lose are moderates who weren’t able to excite the base/ silent majority the way Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and George W Bush did.

The least convincing claim is that this is still an era of Republican dominance. By this argument, after liberalism died with LBJ, Republicans have won 7 of the last 12 presidential elections, and the party is favored to win the next two, as it has been three generations since Democrats held the White House for more than two terms. Democrats only get the White House under the right set of circumstances. Their only successful nominees since Nixon have been Southern Governors, or a rare candidate who fit a very specific demographic sweet spot: a Midwestern African-American elected to statewide office. And the only Republicans who lose are moderates who weren’t able to excite the base/ silent majority the way Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and George W Bush did.

If this were true, you would expect Mitt Romney to underperform relative to conservative candidates like Arizona Senator Jeff Flake, Indiana Governor Mike Pence, Indiana Non-Senator Richard Mourdock and Missouri Not-Senator Todd Akin. That wasn’t the case.

The three scenarios have implications for the 2016 presidential election, as well as the strategies of the major political parties. If we’re in an age of parity, the Republicans are more likely to win, but Democrats have a shot at keeping the White House in the event of a catastrophically bad Republican nominee or fantastic approval ratings for the outgoing President. If this is an era of Democratic dominance, the reverse is true. My concern is that too many Republicans will be comforted by the final argument, and decide to nominate the most conservative candidate the next time around, regardless of the individual’s political gifts, or lack thereof.