Hello, all! After too long of a break, I have returned for more posts about dinosaurs! I thought that I’d start out with a series of posts outlining the various groups of dinosaurs and their relationships to one another. This way, in future articles, I can link back to these descriptions so that you can get a quick idea of the dinosaurs I’m discussing if you missed or forgot about one of the groups.

Ornithopoda, from the Latin for “bird foot,” was named by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1881. They fall within the Ornithischia, or “bird-hipped dinosaurs,” one of the two major groupings of dinosaurs.

Ornithopods include two main types of dinosaurs. The first type is an array of sequentially more “derived” dinosaurs, which means that they have acquired new traits and are slightly higher up on the evolutionary tree. These can collectively be called Iguanodontians. The name for this group comes from Iguanodon (“iguana tooth”), which was the second dinosaur ever named in 1825. Iguanodon has, unsurprisingly, teeth very similar to that on a modern iguana. It also has bony spikes in place of a thumb, likely used for protection. When it was first described, this thumb spike was misinterpreted as a nose horn! The middle three fingers were fused together to form a walking pad, and it had an opposable pinkie that it used for grasping in a similar way to how we use our thumbs. Iguanodon and its relatives likely walked on both two and four legs, depending on whether they were running or walking.

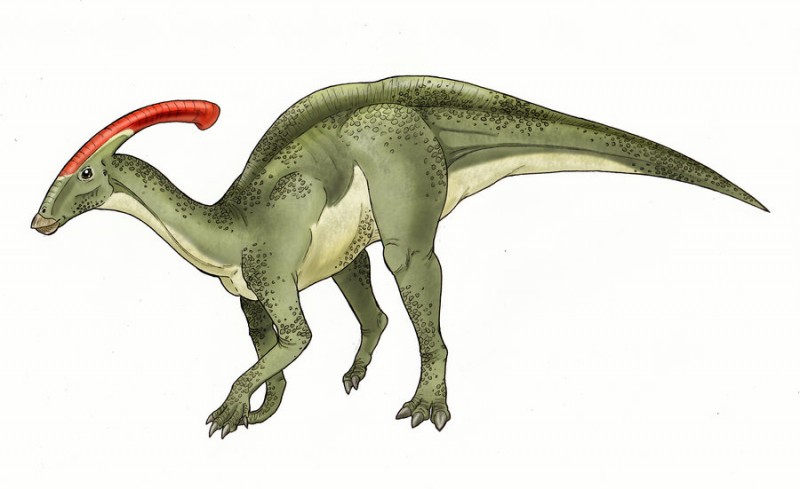

Higher up the tree are the hadrosaurs, which literally means “heavy reptiles,” but which are colloquially known as duck-billed dinosaurs. The first discovered of this group, Hadrosaurus foulkii, was found in Haddonfield, NJ. At the time it was discovered in 1858, it was the most completely preserved dinosaur found anywhere in the world, consisting of most of a leg, most of an arm, a pelvis, a small piece of a cheek bone and some vertebrae. Hadrosaurus foulkii was the first dinosaur to ever have a reconstructed skeleton mounted in a museum, and it’s on display in the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The hadrosaurs are split into two main groups — the hadrosaurines and the lambeosaurines. Both groups have crests on their heads, but they are quite different. Hadrosaurines have solid crests of bone, which were likely solely for display. Lambeosaurines, on the other hand, extended their nasal passages up through their crests, creating a resonating chamber to produce noises, probably for communication. Because of this, lambeosaurine hadrosaurs may be the only group of non-avian dinosaurs whose calls we may be able to reproduce at least partially.

Parasaurolophus walkeri, a lambeosaurine hadrosaur. The nasal passages run all the way up and back down the head crest, producing a low pitch call which could carry over distance.

Ornithopods, along with the marginocephalians that I will discuss next week, collectively form the group cerapoda (a portmanteau of ceratopsia, the horned dinosaurs that fall within marginocephalia, and ornithopoda). This is the group of dinosaurs that possess cheeks, and as a result, both of these groups developed extensive teeth batteries, sometimes with thousands of teeth in a single mouth, along with constant tooth replacement for an incredibly impressive implement for chewing. Other dinosaurs do not chew and instead swallow their food whole, as can still be seen in birds today.

The lower jaw of a hadrosaur, displaying an impressive number of teeth arrayed in rows that would be continually replaced throughout life. (credit: Dave Hone)

If you missed my first post or any of the others, check out Meet the Paleontologist!