Eleven years ago, I reviewed one of my all-time favorite games — 1960: The Making of the President. It was based on an older, even more highly-respected, game often considered one of the top board games ever produced — Twilight Struggle. Twilight Struggle pits two players against one another while taking on the roles of the U.S. vs. the USSR during the Cold War era. It’s a deep, tactical game that often takes several hours to complete and several plays to digest its complexities. That’s one of the reasons that I was drawn to the newer 1960 game. It took the core design of Struggle and simplified it without losing much, if any, of its amazing draw. Both are extremely thematic and so good at their presentation that players often learn about history while taking part. Brilliant!

Eleven years ago, I reviewed one of my all-time favorite games — 1960: The Making of the President. It was based on an older, even more highly-respected, game often considered one of the top board games ever produced — Twilight Struggle. Twilight Struggle pits two players against one another while taking on the roles of the U.S. vs. the USSR during the Cold War era. It’s a deep, tactical game that often takes several hours to complete and several plays to digest its complexities. That’s one of the reasons that I was drawn to the newer 1960 game. It took the core design of Struggle and simplified it without losing much, if any, of its amazing draw. Both are extremely thematic and so good at their presentation that players often learn about history while taking part. Brilliant!

A short while ago, I became aware of a new product from Jolly Roger Games called 13 Days: The Cuban Missile Crisis. Word of the game suggested that it was a lighter version of Struggle, which, of course, immediately appealed to me. I decided to pick it up and give it a spin.

To call this a lighter version of Struggle understates the situation entirely. It goes way beyond that simple description. Upon reading the rules, my initial thought was a bit negative. It seemed as if designers Asger Harding Granerud and Daniel Skjold Pedersen did little more than apply a narrower theme with fewer turns while calling it a new product. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, then this is one flattering product. It’s not as if the games industry hasn’t experienced this sort of cloning process before. Words with Friends is clearly Scrabble, but with a larger online audience. Cards Against Humanity is pretty much just Apples to Apples, but taken to a whole new hilarious level. Was this game more of the former, the latter or something entirely different?

The Box and Components

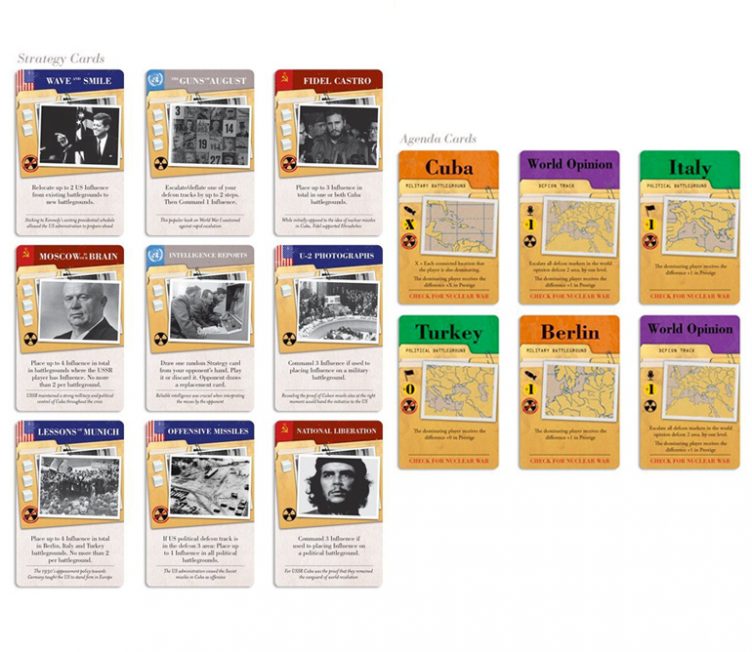

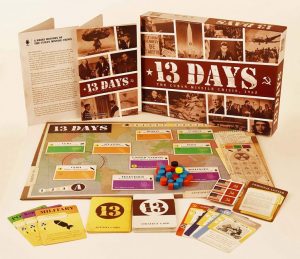

The glossy, sturdy box is slightly smaller in height and width than a typical piece of copy paper. It looks like it can handle some abuse. Inside, you’ll find a basic cardboard insert, a small game board, 13 Agenda cards (13, I get it), 39 Strategy cards (hey, 13 x 3?), one Personal Letter card, 34 small wooden influence cubes (17 blue and 17 red), 6 small wooden DEFCON markers (3 blue and 3 red, although my box actually came with 6 of each), 6 cardboard Flag counters (3 U.S. and 3 USSR), 1 small wooden Prestige marker (to keep track of scoring) and 1 small wooden Round marker. You’ll also find a comprehensive, well-written, 22-page rule book (of which only nine pages are the actual rules and the rest is a step-by-step game overview that I didn’t end up needing), plus a bonus 15-page backgrounder on the actual history of the Cuban Missile Crisis. There are also two advertising cards for other Jolly Roger games and two pieces of foam to keep things nicely separated. The cards are well designed and feature a nice linen finish. The artwork on the Strategy cards is instantly recognizable to anyone who’s played either Struggle or 1960. You won’t find any unnecessary miniatures included, and that’s more than fine with me. What’s here is well thought out and presented.

The Rules

13 Days puts players in the role of either U.S. President John F. Kennedy or USSR Premier Nikita Khrushchev during the tense standoff of the Cuban Missile Crisis (as if you hadn’t realized that already). Each player tries to gain the most Prestige (points) while, at the same time, trying to keep the DEFCON levels low enough to avoid launching nuclear missiles. Any player who launches their missiles is the loser, and that can easily end up being both players. If neither player launches their missiles, then the winner is the player with the most Prestige.

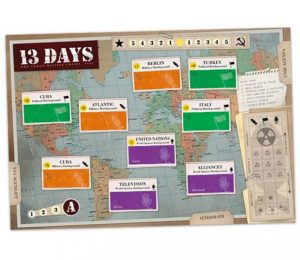

The board includes three Political “battleground areas” (Cuba, Italy and Turkey), three Military battleground areas (Cuba, Atlantic and Berlin) and three World Opinion battleground areas (United Nations, Television and Alliances). The board also includes a DEFCON area that tracks the levels for each of the players in each of the three battleground types (Political, Military and World Opinion). At the start of the game, each player will have one DEFCON marker on each of the three tracks (or columns). The U.S. player also starts with one Influence cube on Turkey and Italy, while the USSR player starts with one Influence marker on Cuba (Military) and Berlin.

The game is broken up into eight phases repeated each round:

- The DEFCON markers are each moved up one space on the DEFCON track toward DEFCON 1. (Each track has a total of eight spaces between DEFCON 3 and DEFCON 1.)

- Each player draws three Agenda cards. These cards will represent the focus of the player for that round. Agenda cards generally relate to the battlegrounds on the board or the DEFCON tracks. For example, the MILITARY agenda card will award that player Prestige points based on how much higher, if any, their Military DEFCON level is above the other player. The TURKEY Political battleground card will award that player Prestige points based on the number of Influence markers they have on Turkey above those of the other player. Each player then places their three Flag counters on the board next to the areas matched by the three Agenda cards that they’ve drawn. This might seem strange at first as you’re now telling your opponent exactly which three cards you’ve just drawn. The catch is that you’ll keep just one of the cards while reshuffling the other two back into the Agenda deck.

- Each player then draws five Strategy cards. After looking them over, the player with the lower score decides who plays first. At the start of the game, this Initiative choice is given to the USSR player. The order of card play can make or break your efforts, so this is no small decision. Sometimes, it’s better to go first, and sometimes, it’s not. Whoever is determined to play first then plays one of their five Strategy cards, then the other player follows by playing one of theirs. This repeats until both players have played four of their five cards.

- The last unplayed Strategy card is then placed facedown under the board to be used in the final Aftermath phase. This phase will award two final Prestige points to whichever player has the most points stored up in the Aftermath cards; thus, it’s important to not just stick your least useful card here each round. I’ll touch on the details of this shortly.

- The player with the most influence on each World Opinions battleground gets a specific bonus. Those bonuses are calculated during this stage.

- Players then simultaneously show their hidden Agenda card and apply any Prestige due. For example, if your Agenda card was the TURKEY card. then you’ll now receive one Prestige point for each Influence cube that your country has on Turkey above the total cubes of that of the other country. If you have four Influence cubes there and the opponent has two, you gain two Prestige points. If you didn’t achieve your agenda, then you’ll get nothing that round.

- Time to check for Nuclear War. Missiles can be launched in one of two ways. First, if either or both players have a DEFCON marker in the DEFCON 1 area, the game is over and that player or players lose. Also, if either or both players have all three of their DEFCON markers in the DEFCON 2 area, the same result happens.

- If the game didn’t end in Armageddon, you then advance the Round marker. There are just three rounds followed by the Aftermath.

It’s important to note that Prestige is tallied on a singular track that runs from five points for the U.S. down to zero and back up to five points for the USSR. Every Prestige point gained is taken from the other player’s total in a classic tug-of-war battle.

Game Play

This is a game all about balance, bluffing and risk. Since the opponent knows which Agenda cards you were dealt, they have at least a one-in-three chance of knowing where you’re hoping to focus your attention. Remember also that you can’t just focus on your own goals, but also need to thwart your opponent achieving theirs. This is done through the playing of the Strategy cards. Each card is made up of several key parts:

- Each card is a U.S.-specific card, a USSR-specific card or a UN card. This refers mainly to the Event text on the card, but during the Aftermath portion of the game, it functions differently.

- Each card has a number of Command cubes shown on it which relates to how many Influence cubes you may alter on the board with that card.

- Each card has an Event that you, or your opponent, may trigger during each play. Some events also affect the DEFCON track.

Strategy cards can be played in one of two ways. All cards can be played for Command. In this case, the number of Command cubes shown will allow that player to affect that many Influence cards on the board, but only in one battleground area or one DEFCON area. The Event text on a card may be triggered by the player only if it is a card from their country or a UN card. If the card is from the opposing country, it may only be played for Command, but the opposing player is given the option of triggering the Event text on that card first. This is a major part of the game play and deviates a bit from both Struggle and 1960. In those games, this can happen, but only for one card each round. Here, if I draw a hand of nothing but my opponent’s cards, he can trigger four of them. That will seem insane to players of the other games, but it’s also one of the most beautiful parts of the design of 13 Days. All of the cards are wonderfully balanced, so even though a bad draw can happen, its impact can be heavily reduced or even eliminated with the right order of play and careful use of the Command/Influence cubes.

I also mentioned the Aftermath stage above. The last unplayed Strategy card is placed into the Aftermath area. After three full rounds of play, this deck is examined. You then simply sum the total of Command cubes shown for each country (ignoring any on UN cards), and if either country has a majority of cubes, they receive two additional Prestige points. It’s quite easy to underestimate the value of the Aftermath cards. Remember that no player can have more than five Prestige points, so these final two points can often be the difference between victory or defeat.

There are two huge game play differences between 13 Days and the other older games. The first is that Influence cubes are not only important to place onto battleground areas, but just as important to remove from them. This might really throw veterans of the other two games at first. Remember that, in 13 Days, each player only gets 17 Influence cubes to spread around and 2 already start on the board. You’ll run out quickly. The only way to get more is to remove them from areas where you feel your influence isn’t currently as important. The second difference is the DEFCON track and how it works. In Twilight Struggle, there’s a mini-game known as the Space Race. In 1960, that same element is The Debate. Both the Space Race and The Debate feel quirky in comparison to their core games. They just feel pasted on. The DEFCON track is an entirely different, totally fascinating experience. It results in play balance that neither of the other two games can match. So how does this work?

Every time you play Influence cubes to battlegrounds via the Command section of a card, you may end up also impacting the DEFCON level. Remember that playing Command limits your Influence cubes to being played to just one battleground area for that card. Placing or removing one cube in an area is considered a minor move and doesn’t impact the DEFCON track for that battleground type (Political, Military or World Opinion). However, for every cube placed or removed above one, the DEFCON track for that type is moved up or down one level less than the total number of cubes moved. If I play a Strategy card with three Command on it and place three Influence cubes in Italy, which is a Political battleground, then my Political DEFCON marker moves up two spaces towards DEFCON 1. If I remove three cubes from Italy, then my Political DEFCON marker moves down two spaces. This is how balance is maintained, and it’s no easy feat. There’s this constant pressure of wanting to maximize your score with more Influence cubes, but then the DEFCON track gets out of hand. Without a constant eye on its status and everything that impacts it, you can quickly end up on the losing side of a nuclear launch.

Conclusion

In the end, where does this leave us? Is this a better game than Twilight Struggle or 1960: The Making of the President? That very much depends on what you’re looking for. From a depth standpoint, 13 Days doesn’t come close to either of its predecessors. However, its key advantage is that an entire game can be played in roughly 45 minutes compared to 90-240 minutes or more for the other games. That advantage alone should guarantee that it appeals to a wider audience and makes it to the table far more often. Where it doesn’t compete as well is in the immersion and theme areas. It just doesn’t have the same aura as its kin. In the other games, I read the flavor text of every card and feel transported into their worlds. In 13 Days, I don’t feel the need or desire to bother with the flavor text. While functional, the board itself does little to help deepen the experience. The battlegrounds are just big rectangles that obscure a nearly-ignored map beneath them. I don’t believe that I ever once thought of any facet of the Cuban Missile Crisis while playing.

There are also a couple of minor missteps that could have eased learning; they boil down to confusing terminology. The game includes a Personal Letter card that plays a small part in the game that I didn’t detail, but there’s also an Agenda card called the Personal Letter Agenda, and confusing the two is far too easy. There’s also the confusion between the term “Command” and “Influence.” It would have been much easier to simply drop all of the references of the former and just call the cubes on the Strategy cards Influence. I also have to mention that it does feel a bit strange to win the game when the loser launches his nuclear arsenal. That’s like trying to wrap your head around a time-travel paradox. I wish that it had a better explanation.

Other than those fairly trivial concerns, this is a wonderful two-player game that you can grab for well under $40. It plays fast and has nice components, a solid rule book and great game play, especially with respect to the DEFCON facet. The designers deserve much praise for creating far more than just a simple clone of a more complex game. This is a winner in its own right.