Days of Wonder (DoW) is preparing to ship a follow-up to its highly-regarded Shadows Over Camelot board game. This time around the designers have taken the original in for a tune-up and reduced it down to a sleek, easily approachable card game aptly named Shadows Over Camelot: The Card Game.

Days of Wonder (DoW) is preparing to ship a follow-up to its highly-regarded Shadows Over Camelot board game. This time around the designers have taken the original in for a tune-up and reduced it down to a sleek, easily approachable card game aptly named Shadows Over Camelot: The Card Game.

For those unfamiliar with the industry this sort of minimalism is nothing new. Other major games have gotten similar spin-offs. The goal with each of them is to maintain the flavor of the original (to draw in existing fans) but to also have it stand out on its own.

Like the original, this game is a cooperative affair with a twist. Unlike most games, Shadows is meant to be won or lost as a group. The twist is that one or two of the players might just turn out to be a traitor who wins or loses in contrast to the rest of the group. Co-op games aren’t for everyone but I’m a definite fan of the genre.

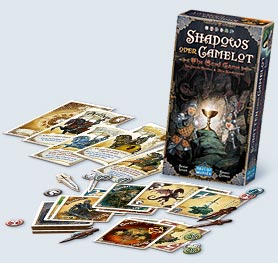

The Box And Components

If there’s one thing DoW is known for, beyond anything else, it’s a commitment to well-designed products often with lots of high-quality parts. Their attention to detail is so high that even when I don’t like one of their games (a rare case thankfully) someone else is sure to want it.

(On a side note, DoW’s customer service is also noteworthy. I contacted them with a very unlikely request regarding my original Shadows game—one I never expected anyone to actually meet—and yet, some time later, they did so without question. Thank you Madison!)

In this specific case we’re talking about a card game with minimal pieces so there really isn’t much elbow room for them to work their full magic. That said, the box is their typical thick stock with a nice feel and excellent artwork. Gamers will appreciate the minimalist, and yet effective, insert just right for every item. The card stock is hearty, well designed and likewise sports apropos artwork. There are some cardboard pieces but they’re entirely reminiscent of the original’s cardboard pieces.

In this specific case we’re talking about a card game with minimal pieces so there really isn’t much elbow room for them to work their full magic. That said, the box is their typical thick stock with a nice feel and excellent artwork. Gamers will appreciate the minimalist, and yet effective, insert just right for every item. The card stock is hearty, well designed and likewise sports apropos artwork. There are some cardboard pieces but they’re entirely reminiscent of the original’s cardboard pieces.

The box itself makes it pretty clear that this is an multinational product sporting English on the main cover with German and French on the sides.

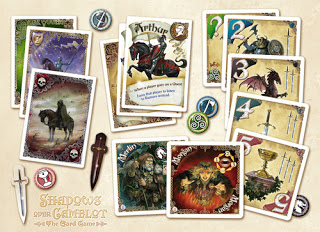

There are three types of cards that come in two sizes and shapes. First and foremost are the 62 square Rumor cards which represent the bread and butter of the core game. There are also nine Knight cards (in typical playing card shape) meant for advanced play and nine Loyalty cards (seven “loyal” and two “traitor”).

There are actually 27 Knight cards in all as you get three sets—one in each of the core languages. The cards include a bit of necessary text which explains the need for different versions. This seems like a nice touch but could also be a slight minus as you’ll always have these extra—mostly useless—cards to deal with on each play.

You’ll also find 16 cardboard swords (for scoring) and 10 cardboard tokens (two for each of the five different types of quests you can embark on).

Finally there’s the multilingual rules book that’s of typical DoW quality and clarity. I had only one slight bit of confusion on the first read through but that was cleared up almost instantly upon a slight trial run of the game.

The Rules

After digesting the rules I had some initial reservations. I was concerned that too much of the original feel was sacrificed and it read as if much of the play hinged on this being a memory exercise. The problem there is that my gaming group includes a player or two with near-photographic memory that often destroys any such games.The next several paragraphs essentially cover the key elements of the rules so feel free to skip a bit down to Game Play if you’d just like to know how it all played out.

After digesting the rules I had some initial reservations. I was concerned that too much of the original feel was sacrificed and it read as if much of the play hinged on this being a memory exercise. The problem there is that my gaming group includes a player or two with near-photographic memory that often destroys any such games.The next several paragraphs essentially cover the key elements of the rules so feel free to skip a bit down to Game Play if you’d just like to know how it all played out.

The first step is to find out if you’re loyal or a traitor. With 2-6 players you one more loyalty cards than players and shuffle in one traitor card. Then you randomly deal them out to the players who keep them hidden. Thus, in any game of that size there is likely—but not always—a traitor among you. With seven players you add the second traitor card to the mix guaranteeing at least one traitor and possibly two. This is very much like the original.

After shuffling the Rumor cards the game can begin. On a player’s turn they must choose one of three options: listen to rumors, go on a quest or accuse a player of being a traitor.Every card chosen from the Rumor deck gets turned over and placed, face up, onto the top of a new “Threat” pile. That action ends the current player’s turn. The next player then has the same three options. Most of the Rumor deck is made up of “quest” cards of differing values. The five supported quests are: the Saxons and Picts (worth one sword each), Excalibur and the Dragon (worth two swords), and the Holy Grail (worth three swords).

After shuffling the Rumor cards the game can begin. On a player’s turn they must choose one of three options: listen to rumors, go on a quest or accuse a player of being a traitor.Every card chosen from the Rumor deck gets turned over and placed, face up, onto the top of a new “Threat” pile. That action ends the current player’s turn. The next player then has the same three options. Most of the Rumor deck is made up of “quest” cards of differing values. The five supported quests are: the Saxons and Picts (worth one sword each), Excalibur and the Dragon (worth two swords), and the Holy Grail (worth three swords).

The game is won by completing the quests and getting seven white swords or lost if the party receives seven black swords.

A player considering a quest can only go on a one whose corresponding card is face up at the top of the Threat deck (the “rumor listened to” by the previous player). Basically the ideal time to go on a quest is when the “rumors” (the value of the quest cards) make it more than just idle gossiping (a low sum) but no so high as to represent an embarrassing misjudgment of the threat (a high sum). A player going on a quest then takes the threat deck and sums up all the values of the various cards therein. All cards in the deck are considered. Cards of the quest the player embarked on are considered the primary quest. Any other quest cards are part of secondary quests (and totaled separately).

If the total value of the primary quest is 10 or below then the rumors were just that and nothing more. In other words, you’ve brought disgrace on the group by showing up for something that wasn’t really an issue. The group, as a penalty, receives black swords matching the value of the quest. If the total is 14 or above then the threat was overwhelming and ends in defeat (and black swords). In other words, you waited too long to deal with it. If the total is 11, 12 or 13 then the rumor was real and dealt with effectively giving the players the appropriate number of white swords.

Remember the secondary quests (the quest cards in the Threat pile not associated with the primary quest). These are also summed and, if their total is 14 or more then they two bring disgrace upon the group. Anything lower is simply ignored as pure gossip.

Once a quest is completed the threat cards are set aside in a discard pile and play continues. However, things are not quite that easy.

Also included in the Rumor deck are special cards that are added to the Threat deck just like the other cards. Here you’ll find characters including Merlin, Morgan, Mordred and Vivien. Most of these cards directly impact the outcome of any quests and are resolved at different times as outlined on each card.

Consider the seven unique Morgan cards. All Morgan cards, once drawn, cause all commentary and interaction between players to immediately end. The only way to undo that is for a player to go on a quest or when someone draws a Merlin card. Additionally, every Morgan card has its own special effect.

For example, the first changes the game play so that every player who chooses to listen to a rumor must secretly look at it and then place it, face down (and thus hidden) on the Threat deck. The player can then tell the rest of the group anything they want about what they’ve seen. Traitors now have a chance to lie potentially throwing a later quest into chaos.

The main focus of these cards seems to act as a continual challenge to player’s memory of the Threat deck. To add variety of play the game includes nine Morgan cards but at the start of the game you randomly remove three from play.

The Mordred card acts as a multiplier working against you in the Saxons and Picts quests.

Vivien is an interesting card that, when drawn, the player immediately draws one of the remaining two loyalty cards and passes the other one (without looking at it) to any player he chooses. Now they both have the option of keeping their initial loyalty card or the new one.

Merlin cards work much like Morgan cards. When drawn players are free to once again converse with one another. There are five different types of Merlin cards and each affects the Threat pile in a different way.

Players may also accuse anyone else of being a traitor but each player can only do so once per game. They also are not able to accuse themselves. This action can only be taken once four swords have come into play (no matter what their color might be). If the accusation is wrong then you add a black sword to the table. If it’s correct then you add a white sword.

Traitors, once revealed, can only take one action on their turn. They go about spreading more rumors by drawing two cards instead of one and placing the card of their choice face up on the Rumor deck and discarding the other face down.

Again, play continues until seven white or black swords are placed. However, there’s a chance the game could end with more (of either or both!) if a quest is in the process of being resolved when the seventh sword comes out. All quests must be fully resolved before the game can end. As in the original game all ties go to the black side.

That’s it for the basic game. The rules include an explanation of playing solo. This is the same game minus loyalty cards as you can’t really be a traitor to yourself—at least not here.

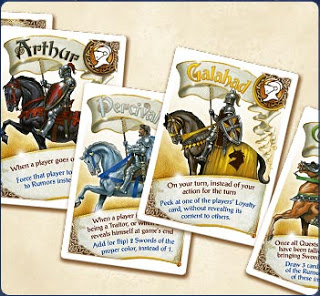

Then there’s the Knights to the Rescue variant which is considered an experts-only option. The idea is fairly simple. Shuffle all 9 of the Knight cards of your chosen language and then also take the three Morgan cards that weren’t placed in the Rumor deck and set them to the side. Whenever a quest is successfully concluded shuffle one Morgan card into the Rumor deck. Whenever a quest fails you draw one of the Knight cards. The questing player reads the card and keeps it hidden until they see fit to play it.

Then there’s the Knights to the Rescue variant which is considered an experts-only option. The idea is fairly simple. Shuffle all 9 of the Knight cards of your chosen language and then also take the three Morgan cards that weren’t placed in the Rumor deck and set them to the side. Whenever a quest is successfully concluded shuffle one Morgan card into the Rumor deck. Whenever a quest fails you draw one of the Knight cards. The questing player reads the card and keeps it hidden until they see fit to play it.

These cards include three Arthur cards, two Tristan cards, two Gawain cards and one card each for Galahad and Percival. Each card has a specific time it can be played and a unique effect. Tristan, for example, is played on your turn before deciding what action to take. It allows the player to look through the Rumor deck and then, after replacing the deck as you found it, you can inform everyone of what you saw.

Game Play

The game itself is fairly simple to play but surprisingly difficult to master—at least after our first several forays.

The most concerning element we ran into was in explaining it to new potential players. Most everyone we described the concept to wasn’t very sold on the idea of it. Seeing it in action changed all of that. Most onlookers then wanted their own shot and joined in for a later game. I think the issue is that it sounds so much like a simple memory exercise but it’s so much more than that.

Another element players found initially confusing was the “benefit” of Merlin cards. For the most part they act to reduce the sum of various quests. Your first thought is that keeping track of everything is already hard enough without our supposed ally adding to the confusion. However, after playing you realize that lowering any sum is better than adding to it as a lower number means it’s not beyond help and potentially (in the case of secondary quests) less likely to cause cascading failure issues.

The communication element (and throttling of it) is a great addition but it’s also one that needs to be strictly enforced. It can be quite a challenge for players to not react while another player, lacking input, opts to listen to more rumors when you’re certain they should instead choose to go on a quest.

In fact, this play element was so strong that we had to remind the group that, once a Merlin was drawn or a quest was completed, it was okay to resume the dialog!

Another minor complication is due to the somewhat close color choice for Saxons, Picts and Excalibur. All are shades of green and that made keeping them straight difficult at times. We had several discussions on whether this was a simple oversight or an intentional design choice.

We also found it quite frustrating (in a good way) that the most simple distraction (like someone asking for a card clarification) would cause you to instantly forget something you were desperately trying to remember.

There’s also a potential “run-away train” possibility where we’re pretty sure it’s virtually impossible to recover. In one play we went from just five white swords to losing the game on a single quest. This happened when the threat pile grew too large as we hoped against hope that something would bring it back to reality. It’s clearly a nice play element that we enjoyed but it’s good to watch out for.

We also never bothered with the basic game and started right off with the Knights to the Rescue variant which we found a breeze to add and more interesting.

In our several plays almost everyone took to the game quickly. Any initial concerns evaporated—replaced by the desire to overcome the challenge. Laughter and tension were in high abundance. However, after a long night of repeated plays I can tell you I felt as if I ran a mental marathon (which I had). I was worn but quite impressed and exhilarated.

Conclusion

Much of my fanaticism for the original is due to the amazing depth of theme. I’m a sucker for a strong theme and will often enjoy a lesser game with a great theme than a great game with a lousy theme. The theme here is fairly light as there’s almost no way a card game can possibly encompass the depth present in the original. The rules make a mild attempt to add some flavor by suggesting that players speak in a chivalrous manner but, of course, that’s going to be a hard sell for some.

For me, the end result is that this entry pretty much is a distinct game in and of itself with only the most basic ties to the original. Thus it only makes sense to consider this without giving much thought, if any, to its ancestor.

Viewed in its own right this game should prove a worthy selection for many. Our friends with exceptional memory fared no better than less memory-gifted players. Many wanted to play it over and over again. Each play felt very fresh and rewarding—even when we lost in a landslide. I suspect some will simply turn off to the concept and stay turned off never giving it a real shot but, for us, this looks like it could be a game we’ll turn to from time to time. I can recommend it for those who are looking for a different filler game.

This isn’t Shadows Over Camelot: Light. If that’s what you were hoping for don’t look for it here. Instead understand that some of the core elements will remain (traitors, earning swords, etc.) but forget the rest and take this in as a distinct entity.

It also doesn’t hurt that it doesn’t require a major time investment. Where the original can easily take two hours to play this one claims to be playable in just 20 minutes. I found 30-40 minutes to be more accurate. Also, unlike the original, it’s extremely portable. You could take this just about anywhere and teach it to players in a matter of a few minutes. The original often will take as long to explain as this takes to play.

Shadows Over Camelot: The Card Game should be available shortly (it’s available for pre-order now) and retails for $25. It supports one to seven players ages 8 and up.