A narcissistic safe-cracker with a notoriously short fuse is released from prison and is determined to set things right in Dom Hemingway.

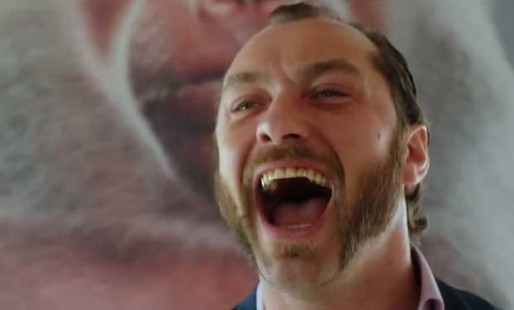

Have you ever met someone who goes out of their way to consider everyone around them? Always careful to not say anything to put someone off or to make anyone feel uncomfortable? Well, that’s not Dom Hemingway (Jude Law). The most efficient means of describing this larger-than-life presence would be “psychotic poet.”

If you have any doubts, rest assured that they’ll be fully and permanently laid to rest with the very first scene. In it, Dom spouts off the most original, most peculiar ode to an appendage I’ve ever witnessed on screen or off. It’s not just the prose. It’s the entire way in which he presents it, complete with an unexpected but entirely apropos finish. It’s the kind of scene that etches a permanent residual image in your mind.

Now free, Dom plans to reconnect with his estranged daughter (Emilia Clarke) and to get a hearty reward from his old boss, Mr. Fontaine (Demian Bichir), for his 12 years of silence. He meets up with his old partner Dickie (Richard E. Grant), and the two set off on a surreal adventure that only a demented delinquent could rationalize.

The film, written and directed by Richard Shepard, is highly stylized with an immediately recognizable look and feel. It suggests the type of film that you’d get from a callous, cynical, coked-up Wes Anderson. The success or failure of the film is entirely in Law’s hands. This is, without question, a one-man show. Law embodies a character that dominates the screen and demands our rapt attention. His signature look, mannerisms, apparel and commentary all work together to cast a spell over the audience. It’s the best bad guy since Ben Kingley‘s Don Logan in Sexy Beast. How good is he? Three quarters of the film flies by with Dom continuing his outlandish antics before you realize it’s all been rather pointless.

Only when the film shifts gears to focus on the story between Dom and his daughter do we recognize just how mesmerizing the experience has been. It’s like the feeling you get when you wake up from a realistic dream and need a moment to get your bearings. As with the dream, the film was more interesting before the reality check. Once you awaken, it’s suddenly no longer quite as stimulating.

On the whole, it’s a very witty, very memorable look inside the head of a person you pray doesn’t actually exist but that you know, deep down, does.