People who go to flea markets dream of the day that they buy an innocuous painting for $5 that turns out to be a valuable work of art. You hear these stories every year, and other modern equivalents involve treasures found in the contents of houses in estate sales or in storage lockers as seen in TV shows like Storage Wars. An amateur historian was looking for old local pictures to put together a book about a neighborhood in Chicago when he stumbled upon a find of immense proportions to the art community. He bought a stash of what turned out to be over 100,000 prints and developed negatives in a lot at auction, and he uncovered the life work of a brilliant street photographer who had been previously unknown. With a feel that’s almost like the reverse of the process in the Oscar-winning Searching for Sugar Man, Finding Vivian Maier is part detective story and part biopic of a fascinating artist as it completely enthralls you for its short running time.

In most cases, a story like this ends up in the pages of a high-profile newspaper or as a featured segment on 60 Minutes. Both of those appearances will probably also happen as people learn about Vivian Maier through this movie, and there has already been one 60 Minutes piece. Produced, written and directed by John Maloof & Charlie Siskel, the film carefully chronicles the mystery surrounding its subject as investigated with great vigor by Maloof, the historian who discovered Maier’s work. Maloof is both part of the story as well as the impetus for it, so there’s no better interviewee than him to describe how things transpired. Like the best documentaries, there are multiple layers of discoveries as the film plays on, and I found myself wanting so much more.

I’m not going to go into detail because that would ruin the movie experience. There are basic facts about Maloof’s efforts and Maier that I can discuss, and they’re crucial to understanding why this documentary is so good. Nobody would know about Maier’s photos if Maloof didn’t have a good eye for this kind of thing. He posted some photos online to solicit photographers’ comments, and he was overwhelmed with the responses. That kicked in his curiosity, and he expertly tracked down any details he could find in the storage locker like receipts from cleaners and phone numbers (without area codes, of course). One thing led to another, and Maloof learned that Maier worked as a nanny for various families over decades and indulged in her passion for taking photos in every other moment of her life. A self-portrait of the person and the artist slowly emerged as Maloof followed the clues in the possessions that she left behind. It makes you wonder what people would think about you if they went through all of your items after your death as methodically as Maloof did with Maier’s things.

At some point in time, Maloof and Siskel decided to make a film about Maier’s life and Maloof’s discovery of her history and artistry. Through a succession of interviews recorded for the documentary, the filmmakers put together a more intricate collage of Maier’s life and behaviors for the audience. The interviewees include children — now adults — in Maier’s care, noted photographers like Mary Ellen Mark and Joel Meyerowitz and even a certain surprise Chicago celebrity, who employed Maier for a year. There are plenty of commonalities like Maier’s quiet nature, her questionable French-like accent and her Rolleiflex camera always being strung around her neck. Things get a little murky when certain charges of hers talk about their punishments or her peculiarities perhaps associated today with hoarding or depression. You could have 10 people describe an elephant and get 10 very different descriptions. The interviews are that divergent, and Maloof tracks down as many of the facts as he can to verify them or debunk them. It’s interesting that both Maier and Maloof become the subjects in this film when they’re also used to being on the other side of the camera.

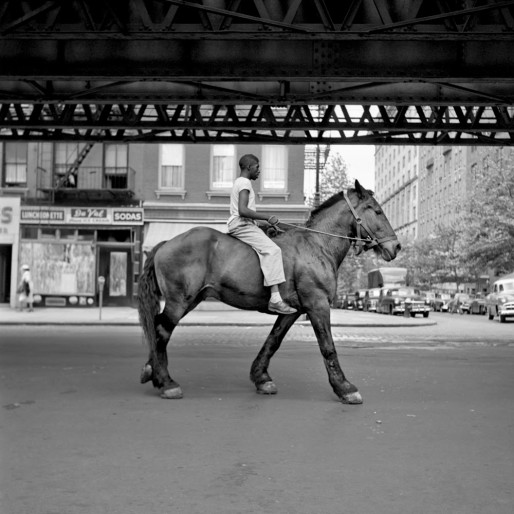

The sheer volume of negatives and images will take years to fully develop, assemble and catalog. It’s almost as if Maier shot as many images with film as people do today with digital cameras and the ability to delete pictures. Her style is distinct and focused with mostly black-and-white images, and each snapshot tells a little story, whether it’s of a man on a horse in the middle of the street or one of her charges hiding from her camera. There are also many amazing self-portraits — what we would call “selfies” today — of Maier taken from tripods or caught in mirrors or windows. She also had a strong command of shadows. Perhaps a little frumpy, Maier nevertheless makes for a fascinating subject through the lens of the camera as well as the focus of a film. The movie touches upon the snobbery of the art community when it comes to Maier. At first, Maloof has a tough time exhibiting her work in galleries, which only cater to living photographers or images that deceased ones developed, printed and approved prior to their passing. Much of Maier’s work was unseen even by her, so the galleries and museums initially want nothing to do with her. Her popularity will change that attitude over time, especially as people realize that she was one of the 20th Century’s greatest photographers.

This documentary packs a lot of content into its short 83 minutes, much like Maier shoved all of her belongings in whatever rooms she occupied as a nanny. Near the end, Maloof starts to open up the film to other events in Maier’s life. It would have been better to extend the film to explore those areas or at least provide a quick slide show of her best work organized by subject matter. Maloof uses interesting visuals to show the number of items he found in the storage locker by laying out similar items like keys or uncashed checks in a matrix, so it’s clear that Maier’s life’s work is in safe, capable hands. There’s perhaps an additional documentary that could be made about the ramifications of Maloof’s discovery on his life and his new role as the caretaker of Maier’s work. Vivian Dorothy Maier lived two lives and was equally dedicated to both her vocation and her avocation. Finding Vivian Maier is the first exposure in the appreciation of her life and art.