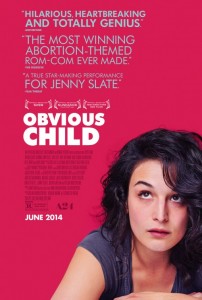

A straight-talking, unfiltered New York comedienne’s one-night stand brings an unanticipated focus to her life in Obvious Child.

Donna Stern (Jenny Slate) is a take-charge kind of woman, albeit with often dubious effectiveness. Even though her Mom thinks she should be doing more with her 780 SAT score, she prefers the challenge of the local comedy circuit, where she can stand up and wax poetically about her love life, her bodily functions and her genitalia. It seems to be her way of telling the rest of the world to take their rigid conventions and pawn them off on the next gal. She’s not interested.

Everything’s going as planned until she’s unceremoniously dumped by her boyfriend and cut loose at her daytime job. Only then does the depth of her situation begin to cast doubt in her mind. Has she been going about this life thing all wrong? Her parents are of no help. They haven’t understood the rhythm of her solitary drum track practically from the start. It all weighs heavily until a life preserver appears in the form of an angelic suitor named Max (Jake Lacy). Their one-night stand offers up the perfect jolt of self-validation that Donna so badly needs. Of course, life’s problems rarely find resolution in such simple measures. Everything, we grow to learn, comes with a cost.

Relative newcomer Gillian Robespierre has written and directed an introspective film about choices and one’s ability to live with them. She also seems to have found the perfect muse for her creativity in Slate, who effortlessly conveys the deeper currents of the material. It’s just a pity that the material isn’t as dependable as its effervescent star. It moves continually between genuine grittiness and contrived nonsense. It feels as if Robespierre spent all her effort on the main concept while ignoring the supporting details.

Beyond Donna, everyone else comes off like a cardboard cutout, hastily assembled from an afternoon daydream. There just isn’t any depth to them, and it cuts both ways. For example, Max is the quintessential Prince Charming. He’s so singularly innocent that we can’t begin to understand what he sees in Donna and vice versa. With such underdeveloped characters, the film struggles to fill the dead space. Sadly, it tries to do so with painfully long pauses and drawn-out dialogue that surrounds the film with a general sense of malaise.

Fans of contemplative introspection might find much to like here. For everyone else, there’s little to enjoy beyond Slate’s performance.