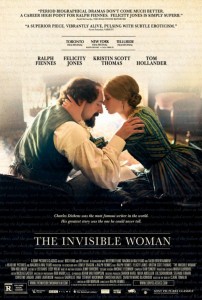

Charles Dickens romances a young, would-be actress who becomes his last great love in The Invisible Woman.

In the second half of the 19th Century, Charles Dickens (Ralph Fiennes) was the toast of England (and the world) as its most successful living author. For all the good his fame brought, what it couldn’t elevate was his estranged marriage to the mother — Catherine Dickens (Joanna Scanlan) — of his 10 children.

While directing a play written by his good friend Wilkie Collins (Tom Hollander), Dickens takes notice of a green, 18-year-old actress, Nelly Ternan (Felicity Jones). Nelly is, of course, a huge fan, and the two begin a friendship that quickly develops into a very challenging affair, much to the chagrin and concern of Nelly’s mother Frances (Kristen Scott Thomas).

The film, directed by Fiennes, is presented from the point of view of Dickens’s lover Nelly. It takes place years after his death as Nelly continues to struggle with the lasting impact of their time together. The details of their affair come in several long flashback sequences, beginning with their initial meeting and culminating in the latter years of their relationship.

The first hour of the film reminded me of a popular comedy bit by British comedian Eddie Izzard. In it, he contrasts the differences between typical English and American films of the same subject. The English example is filled with lots of tedious moments of endless angst, while the American version is full of energy, car chases and explosions. For 60 straight minutes, we get the former. Dickens and Ternan posture endlessly in a mind-numbing ritual whose outcome was obvious from the first moment. It’s like watching two wrestlers who don’t seem to recall that wrestling is a contact sport and instead spin around one another for the entire match.

When the tension finally gives way, the result isn’t worth the trouble. Subsequent scenes all feel as if they’re relaying scattershot details through foggy binoculars from a far-off perch. Pesky details, it seems, would simply be uncouth.

Two late scenes are entirely perplexing. We see a calamitous accident on a train being ridden by Dickens and Ternan but for no good purpose that wasn’t already well established much earlier. Then there’s an entirely unnecessary and manipulative reveal involving a costumed character.

Finally, there’s one of the film’s key points — that this is a story of a woman whose exploits have been aggressively erased from history. That’s simply untrue. While many of Dickens’s love affairs have been lost to history, this one has been well preserved.

The irony is that a film so bereft of any depth would try to embody an author so revered for his eloquent prose.