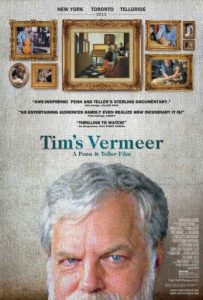

I’ve been a big Penn & Teller fan since I first caught them on TV and went to see them during their frequent stops in Philadelphia with their tours. I think they’re resigned themselves to be lumped in with other magic acts at this point, but for many years, they resisted any kind of classification that could tie them down and instead just enjoyed doing a lot of “cool stuff” for their audiences. That kind of attitude goes back to their earlier years as part of The Asparagus Valley Cultural Society and their experiences and skills more akin to street performers or performance artists than magicians. As a follower of theirs on Twitter, I had read a lot about their film called Tim’s Vermeer. I was excited to finally see what all of the buzz was about with no knowledge of this documentary other than its title and general production statistics. The result is a project that was literally done with smoke and mirrors and fits quite perfectly with the attitudes and skepticism of the duo to earn its moniker as “A Penn & Teller Film.”

Tim’s Vermeer was made almost how Penn & Teller perform. Penn Jillette, the garrulous half of the pair, narrates the movie and produced it with Farley Ziegler (both producers on The Aristocrats). Teller, the quiet sleight-of-hand artist and often the victim of Penn’s stunts, directed the movie over a number of years, presumably during breaks on the team’s performance schedule. The focus of the documentary is inventor and entrepreneur Tim Jenison and his obsession with the works of Dutch master Johannes Vermeer, best known for Girl with a Pearl Earring. Jenison has a background in graphics and technology. His company, NewTek, started out with graphics software for the Commodore Amiga computer and went on to develop the Video Toaster and Lightwave 3D. A fan of art and Vermeer, Jenison couldn’t believe that Vermeer painted without the use of technology, as primitive as it might be. The photorealistic nature of his works and the fine distinctions of color and light point to some superhuman ability or technical aids.

Jenison’s obsession began around eight years ago when he devised a method of painting a near-perfect reproduction of a photograph using mirrors. He thought that his technique could have been used in some version by Vermeer, and he set out on a journey to re-create Vermeer’s The Music Lesson as Vermeer might have painted it. This is one of those goals that only a rich guy like Jenison can pursue. He decided to reproduce Vermeer’s working environment, paints, lenses, window glass and tools down to the finest detail. It’s important to note that Jenison has no skills or training as an artist, so this would be a grand experiment or extended proof of concept.

He transformed a San Antonio, TX, warehouse into a studio almost exactly like Vermeer’s by knocking out a wall and installing the same kind of windows so that light could stream into the studio as it does in a few very similar Vermeer paintings that are all set in the same room. Jenison investigated how to make the same paints as Vermeer and even taught himself how to use a lathe, which he cut in half at one point, to build most of the props and furniture in the composition. As an example of Jenison’s dedication to get things just right, it took him 213 days just to build the room in which he would later paint.

You might think that a film about watching a man paint would be boring and tedious. (Insert “watching paint dry” joke here.) Even worse, the method that Jenison devises is an expansion on the “camera obscura,” so it takes hours to just paint the simplest elements. For example, Jenison spent 130 days to finish the colored spots on a rug in the painting. Fortunately, Teller breaks up the painting scenes with a variety of interviews with notable people, Conrad Pope’s enjoyable score and jaunts for Jenison. Early on, Martin Mull is used as a sort of guinea pig for Jenison’s mirror device, and he’s frustrated that he spent years of painting only for Jenison to come along and do something that almost turns painting into a mechanical task. Jenison travels to Delft, Holland, to investigate Vermeer’s life and haunts, and he somehow manages to get permission to view the original of The Music Lesson, which Queen Elizabeth owns and has hanging in private quarters in Buckingham Palace. (Queen Elizabeth is no doubt a Penn & Teller fan.) More importantly, Jenison shares his technique with artist David Hockney, neuroscientist Colin Blakemore and Professor Philip Steadman. Hockney and Steadman both wrote controversial 2001books about optics in use by the old masters and (for Steadman) Vermeer in particular, so these experts are fascinated by Jenison’s work. Teller also smartly uses Jillette’s comical narration to punctuate the film and lighten the proceedings. Jillette is also perfect to describe the science in the film. Penn & Teller once hosted a Behind the Scenes series for PBS in the ‘90s, and their ability to discuss and break down concepts of visuals, performing arts and music resonates with me even today.

The film created more questions in my head that were unfortunately never answered. For example, how was Teller able to direct the documentary when Penn & Teller have commitments for most of the year at their theater in the Rio in Las Vegas? Even if done during their breaks, this kind of project sucks up a lot of time. With Penn & Teller so used to tricking the audience, I expected a “gotcha” moment, only to find that they were playing this one relatively straight. Still, Penn & Teller often sort of thumb their noses at various figures, so this entire film is right up their alley. Other magicians resent the duo for showing how tricks are done before putting their own spin on them. Those people who complained about the violence in video games were put in their place by the infamous minigame called Desert Bus, perhaps the most nonviolent (and boring) video game ever and a part of the video game Penn & Teller’s Smoke and Mirrors. This entire movie controversially calls out Vermeer for painting with technology and suggests that other artists could have worked this way. The film is sorely missing reaction from the art community. It would be nice to see other people’s reactions to Jenison’s painting beyond its examination by Hockney and Steadman.

Tim’s Vermeer is one of those unexpected delights that develop right before your eyes. In a way, it complements one of Teller’s most famous illusions called Shadows in which he cuts the petals on a flower’s shadow only to have the petals on the real flower fall off. Jenison spent 1825 days painting his version of The Music Lesson, and I wonder how long Vermeer spent on the same work and if Jenison would have continued this task if Penn & Teller weren’t making this movie. Tim’s Vermeer memorializes a fascinating and unique creative process and entertains every step of the way.

3 Comments

I’m not remotely an art expert, but I wonder if a problem with this hypothesis is that most of Vermeer’s famous work isn’t still-life. You can’t have people stand in the same position for hours and hours over the course of more than a thousand days (or maybe you can, I’ve never painted anyone).

lenoxuss The movie does address that issue. Nothing says the people actually had to be there at the same time. Plus the details of the people can be broken into segments. The actual people would only need to be there for a short period to get their faces, hands and so forth. The rest of the time all you need is their outfits on a stand or mannequin.

Agrajag lenoxussAlso note that non still-lifes are less defined and made to appear clear by the usual highlight and glow, a trick well known by the time Vermeer is painting. The curved seahorse pattern was for me undeniable proof that more than an artistic savant he was a smart man that used reason in service of beauty.