On May 5th, 1993, three eight-year-old boys — Stevie Branch, Michael Moore and Christopher Byers — were reported missing and later found hog-tied, naked and submerged in a local stream.

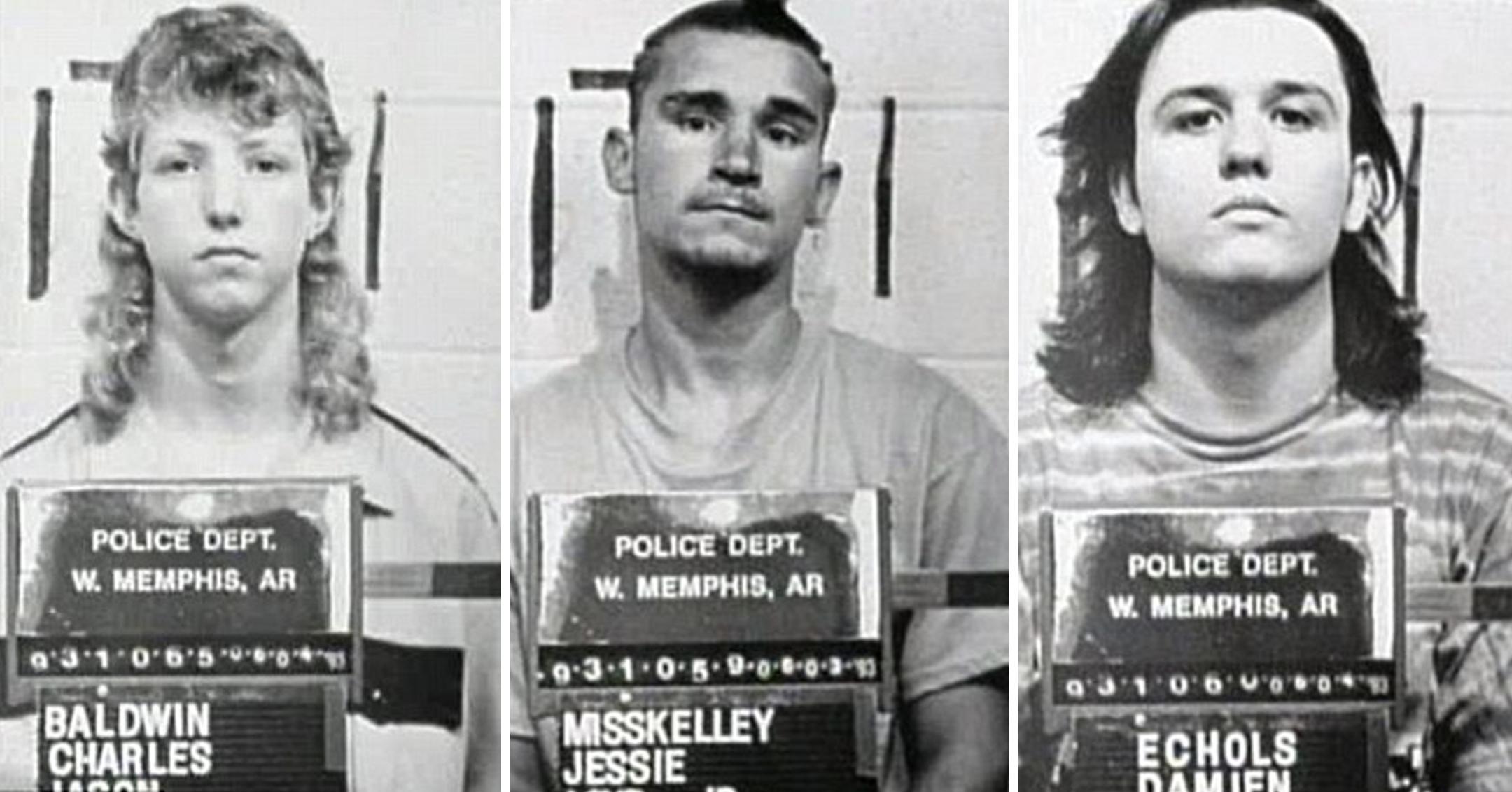

Almost at once, the authorities knew this had all the telltale marks of a satanic ritual killing, and they arrested the most likely suspects — three local teens between 16 and 18 years of age. At the time, there was virtually no doubt anywhere that the West Memphis Three (the convicted teens) were guilty. Much of the surety was due to the actions of one of the three — Damien Echols — who never seemed to miss an opportunity to mug for the cameras or to act inappropriately. He looked about as guilty as anyone could look.

Over the years, as more evidence appeared and crystallized, concerns crept into the minds of many, soon removing virtually any doubt of their innocence in the case.

The film, West of Memphis, takes us from that fateful day nearly 20 years ago and recounts each step. It introduces us to all the key players — from the victims to the accused to the families of the victims, the lawyers, judges and others. Each has a story to tell, and it weaves a tapestry that can only be seen clearly when fully complete.

The path from start to finish is a long one. The film is 2 1/2 hours long, and the first 90 minutes or so seem to drag along aimlessly before finally honing in on the true focus of its main points. We get a full description of the crime, and it’s as heinous a description as anything you can imagine. This is not a film for the faint of heart. Descriptions, documentation and pictures are of the most revealing nature and often quite disturbing, which is very much to the point.

Much of the story is a reminder of the vast reach of this case. We hear quite a bit from people like mega-director Peter Jackson, rock superstar Eddie Vedder and country superstar Natalie Maines, to name a few.

By the time the movie ended, people were just worn out by it. It simply wasn’t presented in the most cohesive way, and it demands a dedication beyond most documentaries. As the allegations of supporters are put forth, you’re at first dubious of them because much of the early story is so haphazard that you can’t help but feel conflicted. As it continues to evolve, it becomes clear that they have, indeed, most likely solved the case for the prosecution, and the West Memphis Three were not responsible. However, there are still a lot of areas that felt unfinished.

We meet Damien’s constant wife Lorri, whom he married while in prison. However, the film entirely glosses over their love affair as if it’s the most normal thing in the world. You can’t help but think what sort of crazy woman would marry a convict on death row, and without addressing the issue, you’re left to doubt much of her commentary for long stretches of the film.

The final act is riveting, and it’s clear that a huge injustice was done and that there have been more victims than originally thought with real justice still to be delivered. However, this effort just isn’t the retelling it could have been and should have been.