In the wonderfully touching 1988 film Cinema Paradiso, the aged projectionist Alfredo laments, “Progress always comes late.” In context, he’s speaking about noncombustible film that’s just come to market too late to have helped in a major fire he barely survived. Today, many wonder if the same isn’t true for current movie theaters and all the recent changes they’ve undergone.

I recently sat down with one of the most experienced projectionists in the country to get his take on all of the changes. His name is Lou DiCrescenzo. Lou is currently the only projectionist for the multiplex in Voorhees, New Jersey, which was recently acquired by Carmike Cinemas and also happens to be my home theater.

Projectionist Lou DiCrescenzo next to one of his beloved vintage projectors

Lou spends just two days a week keeping the projection equipment in peak working condition. Most of that time is spent in very low light in a large rectangular room above and behind the theater seats. It’s bathed by eerie dots of colored lights, piercing a darkness that extends as far as you can see in both directions. There’s a small hum of electronics, but otherwise, it’s disturbingly quiet. You can almost feel the ghosts of past films lurking in the shadows. As you move through the room, you see all manner of fascinating equipment you’d never encounter in daily life. Taken as a whole, it ironically feels a bit like the perfect setting for a chilling horror film.

As for Lou, he’s been in the business for decades and is quickly approaching retirement age. One gets the clear sense that he’s been very lucky to have lasted this long in a career that many establishments targeted long ago as an extravagance. Today, most projection rooms sit empty aside from the whirring equipment that starts, stops and restarts automatically. By contrast, the projectionist of the past was an essential resource — and was paid as such. As technology improved and automation evolved, the projectionist’s role declined along with their fortunes, ultimately ending up as the endangered species they are today.

None of that seems to faze Lou. It’s all just part of the business to him, and it’s a business he loves both as a vocation and as a hobby. Lou’s personal collection of film and film technology includes one-of-a-kind items that grace the inventory of the Smithsonian. He screens his rare original copies of older films throughout the year at various venues, often having to provide his own equipment to run it on. When it comes to the job itself, there’s little doubt that this otherwise cheery, light-hearted spirit is all business. Lou is very much a perfectionist projectionist and wants only the best experience for the audience.

A Barco digital projector

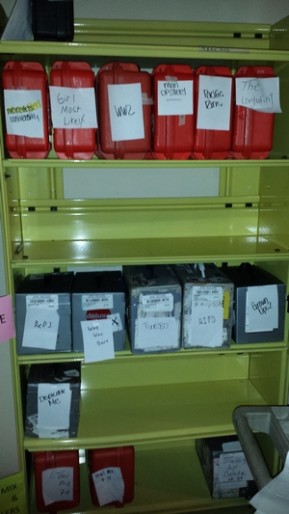

Digital films stored on hard drives sitting in their shipping cases

He spoke both wistfully and wisely about some of the biggest changes in the field during his tenure. The newest change was the move to digital projection systems that burst on the scene three or four years ago. The technology boasts a picture that, unlike before, is free of scratches or degradation regardless of how often it’s run. It also includes dramatic improvements to the audio. Lou, however, thinks a change 40 years ago was possibly bigger. That’s when the industry switched from carbon arc bulbs to newer Xenon ones for the projectors. The older bulbs were much more expensive and required an adept projectionist but provided a less harsh, more pleasing image. When the new bulbs showed up, they were cheaper and provided a more reliable picture without the need for projectionist intervention. It’s like the difference between incandescent bulbs and fluorescent. While the latter is cheaper and lasts much longer, they also aren’t as flexible or as pleasing to the eye as incandescents. In the end, Lou tells me, all the advances are better for the viewer. They end up with a more immersive, more dependable experience, which is what he thinks matters most.

It doesn’t hurt that the latest digital projectors are also evolving more quickly than expected. He noted that the first ones were 2k machines that provided a very low picture resolution of 2048×1080 pixels. That’s only incrementally higher than today’s HD TVs that create an image of 1920×1080 pixels. Imagine taking your HD TV and blowing up that picture to the size of a theater screen. The results weren’t very pleasing. Most digital projectors are now 4k (4096×2160) with 8k units already pushing into the market.

A digital film on a proprietary hard drive sitting in its shipping case

The shift to digital also had a major impact on how movies end up at the theaters themselves. Studios used to ship very heavy reels of films out to countless theaters across the globe. Digital films were first put on proprietary hard drives and shipped to the theaters that then put them into their new library management systems. Such systems dictate when the films can be shown and limit the number of viewings. At the end of their run, the hard drives needed to be shipped back to the studios. Today, the films are being sent out via satellite directly to the theater’s systems without anyone ever needing to touch them. It’s yet another manual process that’s been eliminated leaving Lou and his few remaining peers struggling to validate their own necessity.

As someone who’s been a theater buff for more than 40 years, I can say from firsthand experience that I’ve seen the impact of the demise of the projectionist. No matter where I go to see movies today, I find many more examples of house lights not being turned off, films that start late, the wrong film being shown, audio without a picture, films poorly out of focus or simply nothing at all. These are elements that the projectionist of the past would handle with utmost care. Today, when something goes wrong, the theater usually sends a part-time student worker rushing up to the ever-more-desolate projection room to reboot the whole system. If that doesn’t address the problem, then there’s nothing they can do but call in a contractor to fix it later. Maybe that’s a role the last projectionists can fill. If so, perhaps one of the most respected of them will be Lou. Until then, he’ll be up there providing countless people with a magical experience few really consider beyond what they see on the screen.

If you’d like to find out more about Lou you can search out his own documentary called The Projectionist: A Passion for Film.